By Robin M. Tagliaferri, FHM Executive Director

MyTownMatters and the Forbes House Museum are happy to offer a series of short stories and illustrations on Ireland’s Great Famine and its connection to Milton and Boston. Since 2011, the FHM has been collaborating with scholars and civic groups from the United States and Ireland, researching the Great Famine, which took place from 1845 to 1852. The FHM Great Famine project seeks to raise awareness for the historic 1847 humanitarian voyage of Captain Robert Bennet Forbes (1804- 1889), who transported 800 tons of food and other provisions to Cork, Ireland aboard the USS Jamestown at the height of the Famine.

In the last installment, social and political issues were explored as they related to Boston’s response to Ireland’s Great Famine. At the height of the famine in winter 1847, Bostonians struggled with the looming conflict of slavery and the on-going war with Mexico. Bigotry and anti- immigrant sentiments toward the Irish sparked riots in Boston neighborhoods. Members of the political movement, The Boston Repeal Association, diverted attention from efforts to collect food and cash for famine relief by seeking a long- range political solution- a repeal of the Act of Union (1800) with Great Britain. It seemed that Boston had problems of its own- who would come forward to organize a response to the famine?

Boston’s indifferent and sporadic response to the famine ended, many would say, on 20 January 1847 with the arrival of the Hibernia, a packet ship from Liverpool, England. The press reported a lack of food in Ireland with entire communities dying of starvation, while the British government conceded they could no longer control the situation.

The first native born Roman Catholic bishop of Boston, John Bernard Fitzpatrick (1812- 1866) was among the first to organize a comprehensive famine relief effort for Ireland. On 7 February 1847 in Holy Cross Cathedral, Fitzpatrick read his first pastoral letter, laying out the desperate circumstances in Ireland and pleading for help to alleviate the suffering:

It were needless, dearly beloved brethren, to lay before you the motives which lead to address you. There is no ear that has heard them, and, we trust, no heart that has bled, at the recital. A voice comes to us from across the ocean… it is the voice of Ireland. This hapless country forgets her past griefs, great as they were, because one greater than all has come upon her. She no longer laments her lost liberties… nor complains of the galling fetters that still bind her, but she bewails her sons and her daughters and her little children suffering, starving, and dead…

It is vain and idle, at a time like this, to discuss the causes to which such calamities may be traced. It is vain and idle to discuss of the duties of Parliament and of landlords, and debate whether it is the will or the power that is wanting in them to afford relief. In the meantime, men that are our brethren walk the streets like spectres (sic), crawl over the ground like worms, and die because they have no food…

Let us arise and we shall not be alone; for throughout this vast country all those who love the faith, and all those who love that country of which the cruel sufferings may be ascribed to her inviolable attachment to the faith, and all those whose hearts are warmed by the fire of divine charity, will be at our side; all will act in unison with us. We feel consoled, dearly beloved brethren, with the hope that this appeal will not have been made in vain, we feel the conviction that not one will fail to act nobly and generously his part or to fulfill to the extent of his means what we do not hesitate to call a sacred duty for each one…”

[Taken from The History of the Archdiocese of Boston, In the Various States of Its Development 1604 to 1943, Volume II, by Robert H. Lord, John E. Sexton and Edward T. Harrington, Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston, 1944]

In the 1967 publication, Massachusetts Help to Ireland During the Great Famine, H. A. Crosby Forbes and Henry Lee wrote:

It is said that when the Bishop finished, a terrible silence filled the church, followed by weeping and anguished prayer…. That night Bishop Fitzpatrick called a meeting in the crypt of the cathedral to organize a committee for the entire diocese, later formalized as the Relief Association for Ireland.

The response to his [Bishop Fitzpatrick’s] appeal over the following months forms one of the most extraordinary acts of charity and self-denial in American history. The Irish in America had always been, and always would remain, immensely generous to their connections in Ireland… now in the moment of Ireland’s agony they gave in amounts that, considering the poverty of the givers, almost exceed credibility.

At the end of February Bishop Fitzpatrick transmitted to Archbishop William Crolly (1780- 1849) of Armagh [now Northern Ireland] an initial gift of $20,000, an offering, he wrote, principally of the Catholic clergy and laity of his diocese but also of individual of other denominations. He proposed that the money be distributed by the four archbishops of Ireland in such manner as seemed to them most advisable, not alone to Catholics but wherever want and destitution made claim to its use.

A list of contributors to the Bishop Fitzpatrick Relief Association of Ireland was created through the research of Dr. Catherine B. Shannon, Professor Emerita at Westfield State University and lead scholar in the FHM Great Famine project:

Church of the Holy Cross $6,537.66 St. Mary’s Church, Endicott Street $1,279.66 Catholic Church of Lawrence $281.00 St. Mary’s Church, Charlestown $361.65 Reverend Strain $50.00 Catholic Church of Burlington, VT $442.54 Workers at Revere Copper Co. & Kinsley Iron, Canton $343.00 Reverend John Daly, Bellows Falls, VT $100.00 German Congregation at Suffolk Street $206.80 Catholics of Great Barrington, MA $75.25 Gloucester Railroad Workers $27.00 St. John’s Church, East Cambridge $1,000.00 St. Peter’s Church, Lowell $865.00 Father Mathew Temperance Society $112.00 St. Dominic’s Church, Portland, ME $28.00 St. Mary’s Church, Claremont, NH $64.00 St. Patrick’s Church, Lowell $400.00 St. Mary’s Church, Salem $525.00 St. Mary’s Church, Taunton $553.00 St. John’s Church, Moon Street, Boston $661.00 St. Nicholas Church, East Boston $400.00 St. Mary’s Church, New Bedford $159.00 St. John’s Church, Fall River $600.00 St. Mary’s Church, Cabotville $485.00 St. Patrick’s Church, North Hampton $505.25 St. Joseph’s Church, Roxbury $600.00 Mr. Barnard of Ohio $10.00 St. John’s Church, Worcester $350.00 New Church of Springfield $110.00 St. Peter and St. Paul, South Boston $1,000.00 College of the Holy Cross $200.00 Catholics of Watertown $45.75 Catholics of West Newton $258.00 St. Aloysius Church, Dover, NH $258.00 St. Mary’s Church, Portsmouth, NH $63.50 Catholics of Newburyport $102.50 St. Michael’s Church, Bangor, ME $300.00 St. Mary’s Church, Quincy $266.00 Revere Copper Workers, Point Shirley $128.50

A notable citizen of Boston, Andrew Carney (1794- 1864), clothing merchant, banker and founder of Carney Hospital in Dorchester, was the treasurer for the Bishop Fitzpatrick’s relief association. In the first days of the fund drive, he contributed $1,000, and continued to give unrecorded amounts in subsequent months.

While the churches were doing their part, a groundswell of support for Ireland was being formed within the secular community. In February 1847, poet, abolitionist and Quaker, John Greenleaf Whittier (1807- 1892) wrote in the Boston Pilot (The Pilot was owned by laymen, Henry Devereux and Patrick Donohoe from 1834- 1908), “Wise legislation in the past might have prevented the great calamity… but our duty to relieve present suffering is none less than imperative.”

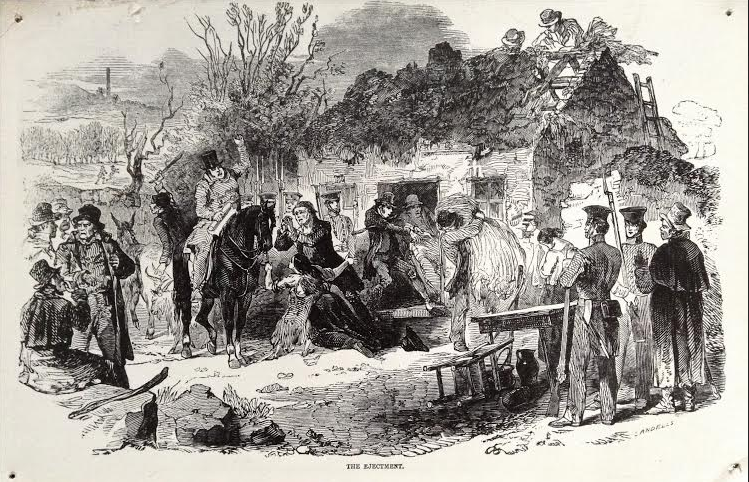

In west Cork, James Mahony (c. 1816- c. 1859), continued his work as an illustrator in the areas most ravaged by the famine. Sent by the Illustrated London News, Mahony captured starvation and its effects, including the ejectment of tenants from their homes.

Ejectment of Irish Tenantry, by James Mahony, Illustrated London News, 16 December 1848.

There are two names associated with this illustration; James Mahony was the creator of the sketch, but Ebenezer Landells (1808- 1860) is cited as the engraver. The engraving process may have been used to transfer the original drawing into an image suitable for newspaper printing. The forms in the illustration are heavier and more densely dispersed than other Mahony illustrations. This printed copy, and the one below, were displayed in the 1967 exhibition at the Forbes House Museum, “Massachusetts Help to Ireland During the Great Famine.” Notice the pin marks at the corners. FHM permanent collection.

A grimly effective rendering of an eviction: the brutal bailiff, the pleading tenant, his weeping wife and children, the unfeeling onlookers and the stony-faced soldiers standing by are all convincingly presented.

Many of the starving found themselves not only without food, but also without habitation. In the pre-Christmas edition of 1848, the Illustrated London News published a scathing article condemning those Irish landlords who were using the current crisis to unpeople their property.

The two illustrations that accompanied the text were engraved either by Landells or by one of his assistants. The first depicted an ejection scene… [it] contains considerable action. We see the tenant remonstrating with the bailiff seated aloft a black steed. Meanwhile, the bailiff’s men are already denuding the roof of thatch, and driving away the tenant’s donkey. Looking on are ununiformed officers. Their presence was intended to ensure that the bailiff was not impeded in his duties, and to discourage civil disobedience. [Taken from The Great Irish Famine 1845-9 by Margaret Crawford]

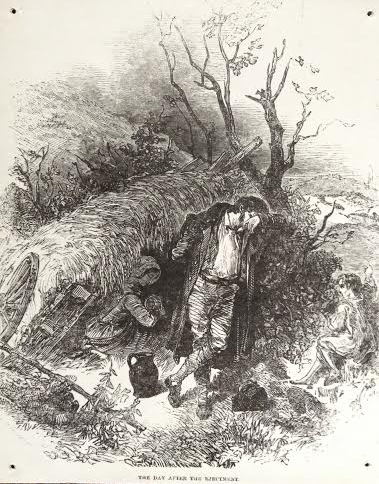

The Day After the Ejectment, by James Mahony, Illustrated London News, 16 December 1848.

A second Illustration shows the make shift shelter along the ditch [a thatched ditch was called a scalp], into which the evicted tenant retreated. The stance of the major figure in the picture is one of utter despair.

The apparent callousness of the landlords stemmed from two major problems. On the one hand they suffered a drastic reduction in their incomes as tenants defaulted on rent. On the other hand they were faced with rising taxation. Circumstances varied from district to district. Nevertheless, some landlords were particularly ruthless, justifying their action by the slogan “evict… debtors or be dispossessed. [Taken from The Great Irish Famine 1845-9 by Margaret Crawford]

The Forbes House Museum is very grateful to 02186/My Town Matters and its editor, Frank Schroth for the opportunity to submit feature articles to the public. A seventh installation in the series, “Forbes House Museum and Ireland’s Great Famine: Who Knows the Story?” will appear later this month.

Sources/Credits for this article include:

Crawford, Margaret, “The Great Irish Famine 1845-9: Images of Reality in Ireland,” Art into History, pp. 75-88, Gillespie, Raymond, ed., Town House, Dublin, Ireland, 1994

Forbes, H. A. Crosby, Ph.D., Massachusetts Help to Ireland During the Great Famine, Captain Robert Bennet Forbes House, Milton, MA, 1967

Lord, Robert H., The History of the Archdiocese of Boston, In the Various States of Its Development 1604 to 1943, Vol. 1-3, Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston, 1944

https://viewsofthefamine.wordpress.com/illustrated-london-news/sketches-in-the-west-of-ireland/

To access previous article in this series:

- Click here to read Part I, providing background information on Forbes House Museum’s association with the Famine.

- Click here to read Part II, giving readers with an introduction to illustrator, James Mahony

(c.1816- c.1859), hired by the Illustrated London News to document the Great Famine. - Click here to read Part III, highlighting the scholars who have contributed to the project thus far and information on James Mahoney’s illustration, Old Chapel- Lane in Skibbereen, County Cork, Ireland.

- Click here to read Part IV, detailing the first humanitarian efforts at the height of the Famine from Boston and from the Society of Friends.

- Click here to read Part V, providing a backdrop to social and political issues in Boston as they related to the city’s response to Ireland’s Great Famine.