By Robin M. Tagliaferri, FHM Executive Director

MyTownMatters and the Forbes House Museum are happy to offer a series of short stories and illustrations on Ireland’s Great Famine and its connection to Milton and Boston. Since 2011, the FHM has been collaborating with scholars and civic groups from the United States and Ireland, researching the Great Famine, which took place from 1845 to 1852. The FHM Great Famine project seeks to raise awareness for the historic 1847 humanitarian voyage of Captain Robert Bennet Forbes (1804- 1889), who transported 800 tons of food and other provisions to Cork, Ireland aboard the USS Jamestown at the height of the Famine.

Beginning in summer 1845, a tragic chain of events took place in Ireland that eventually led to the humanitarian response from Boston in winter/spring 1847, organized by Captain Forbes and the 21 members of the New England Relief Committee. In the publication, Massachusetts Help to Ireland During the Great Famine, H. A. Crosby Forbes and Henry Lee wrote:

Confirmation of the potato loss reached Boston on November 20, 1845, with the arrival of the royal mail steamship, Britannia. Within a few days, local papers carried varied, but uniformly tragic, accounts. “The general prevalence and alarming character of the disease,’ noted the Daily Advertiser, ‘threatens to annihilate [the] supply of this article of food.”

Five days later, on 25 November, Reverend Thomas J. O’Flaherty, pastor of St. Mary’s Church in Salem, called a conference at the Stackpole House in Boston to establish the Irish Charitable Fund, the first formal response to the famine in America. A week later, Rev. O’Flaherty and Rev. James O’Reilly of St. Mary’s Church, Endicott Street, collected $750 at a meeting at the Odeon Theatre in Franklin Street. Contributions totaling $264.64 came from parishioners of the newly consecrated St. Nicholas Church in East Boston, with Pastor Father O’Brien at the helm. Daniel Crowley, a well-known contractor and treasurer of the Irish Charitable Fund, collected $1,100 from his friends and workers.

However, the urgency toward the famine relief began to wane. Many believed that the situation in Ireland had been exaggerated, and famine relief was diverting funds from the movement to repeal the Corn Laws.

The Corn Laws were tariffs on imported grain, including wheat, enacted in Great Britain in 1815 to protect the production and pricing of domestically produced grain. As early as 1845, when the Great Famine entered its first phase, Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, a Tory and Conservative, worked to enact the Importation Act of 1846, a repeal of the Corn Laws. With this action, Peel hoped that imported food supplies would become more plentiful and affordable, alleviating famine conditions.

The dwindling interest in famine support in Boston was due in part to the unexpected death of Father O’Flaherty in March 1846, which halted all activity with the Irish Charitable Fund. Additionally, in spring 1846, it appeared that the potato was once again flourishing in Ireland.

Frighteningly, the blight returned almost overnight in the summer of 1846. Forbes and Henry wrote, “This time the failure was total, and following the partial loss of 1845, presaged a catastrophe deeper and more universal than even long-suffering Ireland had ever known.” Famine and disease moved rapidly across the stricken island by fall 1846 and winter 1847.

The British government instituted various relief measures including a number of public works projects, but none were effective. Adhering to the economic philosophy of laissez-faire, the government imposed no barriers to the free flow of goods, thus permitting the export of Irish grain even during the famine.

“Imports [of grain] were in the hands of private merchants and, while the populace starved, carts laden with wheat and other foods rolled through the countryside under armed guards on their way to Irish ports to be shipped overseas. For the small farmer who sold his grain to pay rent and lived solely on the product of his potato patch there remained no means of livelihood,” wrote Forbes and Henry.

Meaningful famine relief came through the efforts of private charity, and over a two year period, the British citizenry donated over $2.5 million dollars. In 1846, Members of the Society of Friends (Quakers), established soup houses in Ireland’s south east region, stretching to County Limerick.

By all accounts, the contribution of the Quakers was impressive and well organized. The article, “Quakers and the Famine,” published in spring 1998 by History Ireland, Ireland’s History Magazine, sheds light on a network of committees with membership from both Britain and Ireland.

It was with this in mind that a number of Quakers, led by Joseph Bewley, organized [sic] a meeting in November 1846. The outcome was the establishment of a twenty-one member “central relief committee.” To facilitate frequent meetings, membership was confined to the Dublin area, while an additional group of twenty-one would be nominated as “corresponding members” from the Quaker community outside Dublin. Following discussions with their Irish counterparts, Quakers in London also established a relief committee.

Throughout the Famine these two committees worked closely together, with the Dublin committee looking after grants of food and clothing while the London committee raised funds. The division of labour [sic] was not strict, however, and many English Quakers came to Ireland to see for themselves just how bad the situation was and to become involved directly with the giving of relief. As the work of these committees progressed, they set up various subcommittees to handle specific tasks and amongst these were local committees in Waterford, Cork, Limerick and Clonmel which looked after relief operations in the south and south-west.

The Dublin committee kept detailed reports on conditions in Ireland, and for the first time, the scope of the tragedy was revealed to the outside world. Between 1846- 1847, the Society of Friends distributed food and money valuing nearly $1 million dollars, with two-thirds of the total funds coming from the United States.

Unfortunately, the Friends did not have an extensive network to serve the areas most ravaged by famine, the west of Ireland.

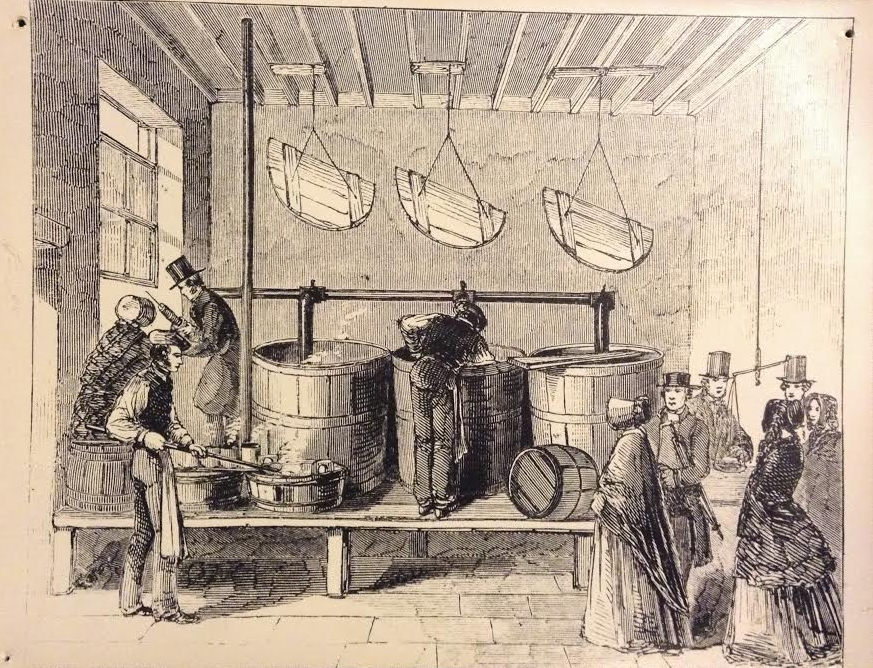

“The Cork Society of Friends Soup House” by James Mahony, Illustrated London News, 1847. “Indeed the contribution of the Society of Friends cannot be overstated, both in the tangible aid it provided to the starving and its major contributions to the historical record of events. These were published in the Transactions of the Central Relief Committee of the Society of Friends during the Famine in Ireland in 1846 and 1847.”[Crawford, Margaret] The Transactions were a reliable source for those seeking to set into context the illustrations in the Illustrated London News. Commentary on this illustration includes questions about the finely dressed people in the right hand corner of the scene, and how the setting seems very peaceful and orderly, despite the fact that famine stricken people were waiting just outside its doors. This actual printed copy was displayed in the 1967 exhibition at the Forbes House Museum, “Massachusetts Help to Ireland During the Great Famine.” Notice the pin marks at the corners. FHM permanent collection.

“The Cork Society of Friends Soup House” by James Mahony, Illustrated London News, 1847. “Indeed the contribution of the Society of Friends cannot be overstated, both in the tangible aid it provided to the starving and its major contributions to the historical record of events. These were published in the Transactions of the Central Relief Committee of the Society of Friends during the Famine in Ireland in 1846 and 1847.”[Crawford, Margaret] The Transactions were a reliable source for those seeking to set into context the illustrations in the Illustrated London News. Commentary on this illustration includes questions about the finely dressed people in the right hand corner of the scene, and how the setting seems very peaceful and orderly, despite the fact that famine stricken people were waiting just outside its doors. This actual printed copy was displayed in the 1967 exhibition at the Forbes House Museum, “Massachusetts Help to Ireland During the Great Famine.” Notice the pin marks at the corners. FHM permanent collection.

An illustrator and watercolorist, James Mahony (c. 1816- c. 1859), worked for the Illustrated London News from 1846-49/50. He was sent to his native west Cork, Ireland, the region most effected by the Great Famine. The printed engravings of Mahony’s illustrations brought shock to readers in England and abroad, documenting the unfolding height of the tragedy and mobilizing public opinion to action.

The Forbes House Museum is very grateful to 02186/My Town Matters and its editor, Frank Schroth for the opportunity to submit feature articles to the public. A fifth installation in the series, “Forbes House Museum and Ireland’s Great Famine: Who Knows the Story?” will appear later this month.

Sources/Credits for this article include:

Forbes, H. A. Crosby Forbes, Ph.D., Massachusetts Help to Ireland During the Great Famine, Captain Robert Bennet Forbes House, Milton, MA, 1967

Boston Daily Advertiser, 25 November 1845

Goodbody, R., Quakers and the Famine, History Ireland, Ireland’s History Magazine, Sandyford, Dublin, Ireland, Issue 1, Volume 6, spring 1998

http://www.historyireland.com/18th-19th-century-history/quakers-the-famine/

Crawford, Margaret, “The Great Irish Famine 1845-9: Images of Reality in Ireland,” Art into History, pp. 75-88, Gillespie, Raymond, ed., Town House, Dublin, Ireland, 1994

To access previous article in this series:

- Click here to read Part I, providing background information on Forbes House Museum’s association with the Famine.

- Click here to read Part II, giving readers with an introduction to illustrator, James Mahony

(c.1816- c.1859), hired by the Illustrated London News to document the Great Famine. - Click here to read Part III, highlighting the scholars who have contributed to the project thus far and information on James Mahoney’s illustration, Old Chapel- Lane in Skibbereen, County Cork, Ireland.

The article looks very wonderful online! Thank you Frank for the beautiful formatting! There’s a lot of important history in the story, and I hope that Milton residents will enjoy it. We will continue to get to the heart of the matter in coming installments!